All that glisters is gold - the Wymondham Abbey altar screen

The parish church of St Mary and St Thomas of Canterbury in Wymondham in Norfolk, is all that is remains of a Benedictine Priory founded in 1107 by Wiliam d'Aubigny, which was raised to abbey status in 1448. When Wymondham Abbey was dissolved in 1538 at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the people of Wymondham were granted as their parish church the nave of the abbey church, the part of the church that for four centuries. The eastern arm was then left to fall into ruin and the arch between the nave and the central tower was roughly blocked in and plastered over, it remained that way until the twentieth century.

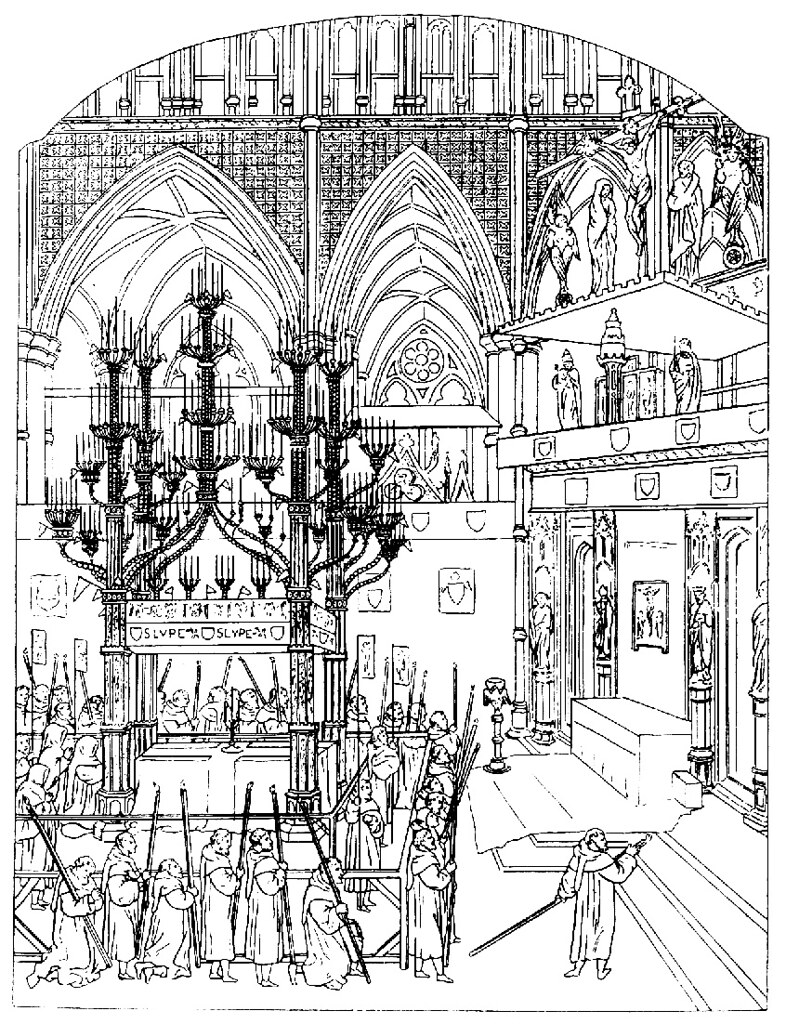

The nave is a splendid piece of Norman architecture dating from 1130, each arch decorated with a different motif and with the whole structure rising to some height through a Triforium and Clerestory. The eastern end of the nave with it's temporary blocking looked rather plain and mean compared to the surrounding architecture and was not a fitting setting for the high altar. In the 1920 Ninian Comper, on the recommendation of Sir William St John Hope, was called in to find a solution to the issue. His solution was to add to the wall an altar screen, with a tester and rood and it is one of his most monumental works. The main part of the work was completed in 1921, although the work of colouring and gilding the reredos was not completed until 1934. The inspiration for the altar screen was no doubt the surviving medieval examples at Winchester, St Albans and Southwark cathedrals. A few years after completing the work here at Wymondham, Comper was to work on the screen at Southwark. The inspiration for the arrangement of the tester and the rood was the pre-Reformation high altar arrangements at Westminster Abbey, as depicted in the Islip roll that records the funeral of Abbot John Islip of the 1532.

Let's have a look at Comper's arrangement here in Wymondahm in more detail. Just as the Eucharist is the foretaste of the heavenly banquet, so Comper intended his altar screen to be a visual foretaste of heaven. The central focus of the screen is therefore a twice life-size image of the Majestas, Christ in Majesty. Christ is seated, his right hand raised in blessing, his feet resting on cherubim and he emerges from heaven in a Mandorla of clouds, his presence emphasised by rays of glory. He gold a book on which are written Alpha and Omega. There are censing angels on the four corners of the panel to herald Christ's appearance.

Around the central image of Christ are two tiers of canopied niches with images of the company of heaven. In the upper part St George, St Etheldreda, St John the Baptist, St John the Evangelist, St Andrew and St Michael.

In the lower tier the central image is an image of the Virgin and Child, Mary being one of the joint patrons of the church. Following medieval precedent here figure is emphasised by being slightly larger than the others. To her right is a figure of the other patron of the church St Thomas of Canterbury. Then from left to right a series of other figures.

Starting from the left and set over two tabernacles, is a delightful Annunciation. The figures of Mary and Gabriel have swaying s-shaped postures similar to figurative work of the fourteenth century and they almost look to be about to step out of their niches.

St Peter is the next figure along from the Assumption and then moving over to the other side of the Virgin and Child, there are figures of both St Alban and St Paul. The four figures that flank the Virgin and Child turn inwards towards her. The whole sequence ends on the right hand side with another composition over two niches the Visitation of Mary to Elizabeth, again both figures have the delightful Gothic swaying posture.

Comper chose a predominately late medieval Gothic and Perpendicular architectural language for this altar screen, but by the 1920s Comper is less rigidly Gothic in his aesthetic expression and here he blends Gothic with Renaissance forms. Next to the screen is an important terracotta sedilia of the 1520s or 30s, entirely Renaissance in detail and Comper was not blind to that. At the top of the screen, just below the coving, each compartment of the screen terminates in a little round headed arch filled withed with Renaissance scalloped decoration.

Projecting from the top of the screen and partly suspended from the medieval roof, is the altar tester. The tester's underside is decorated to give the impression that we were seeing through a window or opening into heaven. In the centre is image of the Holy Spirit, as though about to descend on the altar below, with rays of glory and red droplets of fire issue forth - the pneumatic force of the Holy Spirit. There are also seven scrolls issuing from the central image of the dove, on each is written one of the seven gifts of the Spirit. In the four corners of the panel and witnessing to the power of the Spirit, are four six winged cherubim. Above on the top of the tester are figures of angels with trumpets, heralding the Spirit's descent. It's an unusual and inventive composition.

On the front of the tester is a Latin inscription: 'Dicit in Nationibvs Regnavit a Ligno Devs' - 'We see God ruling the nations from a tree', taken from the hymn Vexilla Regis by Vernantius Fortunatus.

As we absorb this inscription, the image Christ reigning from the tree comes into view above, for one bay forward of the screen is a rood beam and on it a rood group.

Christ Crucified is here flanked as usual by Mary and John and on either side two Seraphim standing on wheels. As stated above, Comper's inspiration for the tester and the rood arrangement was the high altar at Westminster Abbey as shown in the Islip roll of 1532. The arrangement of the rood with the Seraphim is taken directly from the Islip illustration.

The polychromy and gilding of the altar screen wasn't completed until 1934. As withe the iconography the colouring is masterly and is carefully considered to give a rich but not overwhelming effect set within the whiteness of the Norman abbey church. Comper has used both flat and burnished gold and gold leaf with different dominant hues for the gilding. He uses cooler yellow gold for the tabernacle and architectural work and a gold with a red base for the drapery of the figures. Except for the odd bit of heraldry here and there and the flesh tones of the figures, the gold of the drapery provides the only injection of red tones into the whole of the screen's decoration. All the grounds for example are in various tones of blue and there is sparing use of a rather muted brown-murrey and a toned down green in certain areas. It is the combination of the different tones of gold and their finishes and the varying blue grounds, that give the work it's richness - but it is not an overpowering richness.

Comments