Cerecloth, pledgets and grave goods - the burial of William Lyndwood.

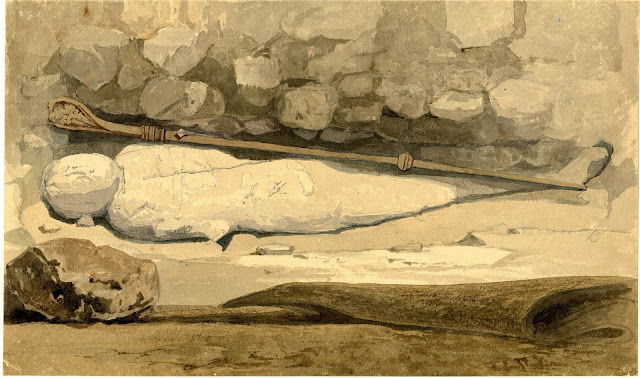

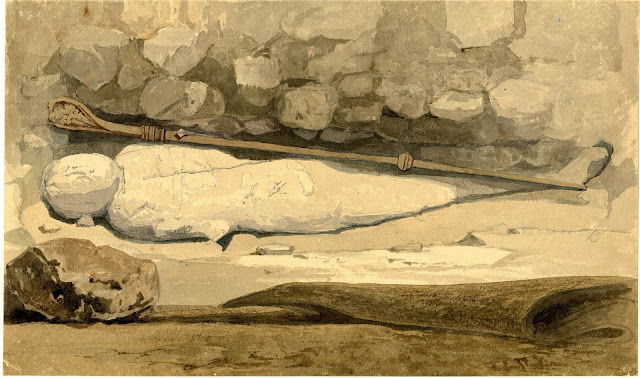

In January 1852 builders were in the process of demolishing the medieval chapel royal of St Stephen in the palace of Westminster and were removing the walls of the medieval undercroft chapel. As they worked, they discovered an extraordinary burial. In a rough hewn cavity in the thickness of the rubble wall, they found an uncoffined body wrapped up tightly in cloth and looking for all the world like an Egyptian Mummy. Laid across the body diagonally was a wooden crosier or pastoral staff, indicating that the burial was probably that of a bishop.

Rather excited by this unusual discovery Charles Barry the architect, called in the Society of Antiquaries and on Friday the 23rd of January 1852 they sent a delegation of their members to examine the find. They brought with them G. F. Scharf, whose drawings and lithographs illustrate this post. The delegation noted that the burial of the body was unusual, it had been placed in an excavated cavity in the rubble wall and that no attempt had been made to create a vault. It's location was just a few inches below the surface of the chapel floor and directly under a stone bench, that ran round the inside of the chapel. In other respects the body's positioning was indicative of the individual's evident high status, for it was under the window in the north wall, close to the site of the undercroft chapel's altar.

The delegation decided that they would come another day to further examine the remains, once they had been removed from the wall.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Rather excited by this unusual discovery Charles Barry the architect, called in the Society of Antiquaries and on Friday the 23rd of January 1852 they sent a delegation of their members to examine the find. They brought with them G. F. Scharf, whose drawings and lithographs illustrate this post. The delegation noted that the burial of the body was unusual, it had been placed in an excavated cavity in the rubble wall and that no attempt had been made to create a vault. It's location was just a few inches below the surface of the chapel floor and directly under a stone bench, that ran round the inside of the chapel. In other respects the body's positioning was indicative of the individual's evident high status, for it was under the window in the north wall, close to the site of the undercroft chapel's altar.

The delegation decided that they would come another day to further examine the remains, once they had been removed from the wall.

On further examination it was evident that the body had been wrapped with great effort and care. Between nine and ten layers of cere-cloth dipped in wax were used to cover the body and this had solidified into a mass that had to be cut to gain access to the contents within. The trunk, head and legs were individually wrapped in layers and then the body was secured along it's length with twine, knotted in various points with a half-hitch knot. The upper arms were wrapped in with the torso, but the lower arms appear to have been left free and the delegation concluded that this was in order that the body could be positioned to hold the crosier.

|

| William Blake's drawing of the body of Edward I, wrapped in its cere cloth. http://www.blakearchive.org/copy/pid?descId=but1.1.penink.01 |

Such tight wrapping in cere-cloth was a known practice for royal burials. When the tomb of Edward I in neighbouring Westminster Abbey was opened in 1774, his body was found tightly wrapped in a cere-cloth as is shown in the image by William Blake above. The crown was placed on the wrapped head of the king and the mortuary sceptres placed on his body, much as the crozier was placed on the body we are discussing here.

The delegation took particular care unwrapping the head. Under the outer layers of cere-cloth, they discovered that the head had been individually wrapped with a layer of canvas forming a kind of mask. This had been tied onto the head with twine.

When this was removed the perfectly preserved, but blackened face of the individual was revealed. It was the face of an elderly man and his mouth was stuffed with a 'pledget of tow' imbued with wax, which protruded from the mouth. Scharf was able to take a death mask, which is still in the possession of the Society of Antiquaries. On the death mask you can still see clearly the indentation in the cheek where the pledget of wax had pressed into the side of the face. What the purpose of the pledget of tow was is difficult to say, it may have been thought to aid in the preservation process.

The cere cloth was cut away to expose the body, with the hope of finding some grave goods that might help identify the body. Unfortunately there weren't any. What they did discover was that there wasn't any evidence that a solution or dressing had been applied to embalm the body and the entrails and organs were still in place. For the most part the body had turned to grave wax or adipocere.

The seemingly deliberate positioning of the pastoral staff was a strong indication that the individual was a bishop. The pastoral staff, which is now in the British Museum, has a carved oak head and a deal shaft. There is no evidence that it was painted or gilded and the use of such cheap materials might suggest that the pastoral staff was specifically made as a mortuary crosier.

The decoration of the head of the pastoral staff is rather conventional. The crook is in the form of a crocketed bent branch, filled with stylised oak leaves. The carving is rather flat and a date in the middle of the fifteenth century seems likely.

The burial by its location and the treatment of the body was that of a high status individual, the pastoral staff suggesting that it was the burial of a bishop, but who was he? Given the stylistic date of the pastoral they knew they were looking for someone who died in the middle of the fifteenth century. The delegation from the Society of Antiquaries came to the conclusion that this was the body of William Lyndwood, the canon lawyer and sometime bishop of St David's. The supporting evidence for this conclusion is quite compelling.

References

The account of the discovery: 'Report of the Committee appointed by the Council of the Society of Antiquaries to investigate the circumstances attending the recent discovery of a body in St Stephen's Chapel, Westminster' in Archaeologia 34 (1852), pp. 406-30.

The delegation took particular care unwrapping the head. Under the outer layers of cere-cloth, they discovered that the head had been individually wrapped with a layer of canvas forming a kind of mask. This had been tied onto the head with twine.

|

| The death mask. |

When this was removed the perfectly preserved, but blackened face of the individual was revealed. It was the face of an elderly man and his mouth was stuffed with a 'pledget of tow' imbued with wax, which protruded from the mouth. Scharf was able to take a death mask, which is still in the possession of the Society of Antiquaries. On the death mask you can still see clearly the indentation in the cheek where the pledget of wax had pressed into the side of the face. What the purpose of the pledget of tow was is difficult to say, it may have been thought to aid in the preservation process.

The cere cloth was cut away to expose the body, with the hope of finding some grave goods that might help identify the body. Unfortunately there weren't any. What they did discover was that there wasn't any evidence that a solution or dressing had been applied to embalm the body and the entrails and organs were still in place. For the most part the body had turned to grave wax or adipocere.

The seemingly deliberate positioning of the pastoral staff was a strong indication that the individual was a bishop. The pastoral staff, which is now in the British Museum, has a carved oak head and a deal shaft. There is no evidence that it was painted or gilded and the use of such cheap materials might suggest that the pastoral staff was specifically made as a mortuary crosier.

The decoration of the head of the pastoral staff is rather conventional. The crook is in the form of a crocketed bent branch, filled with stylised oak leaves. The carving is rather flat and a date in the middle of the fifteenth century seems likely.

William Lyndwood (centre) on the brass to his parents in Linwood, Lincolnshire.

The burial by its location and the treatment of the body was that of a high status individual, the pastoral staff suggesting that it was the burial of a bishop, but who was he? Given the stylistic date of the pastoral they knew they were looking for someone who died in the middle of the fifteenth century. The delegation from the Society of Antiquaries came to the conclusion that this was the body of William Lyndwood, the canon lawyer and sometime bishop of St David's. The supporting evidence for this conclusion is quite compelling.

|

| A copy of Lyndwood's Constitutions, in the library of his cathedral church in St David's. |

Lyndwood was the son of a wealthy Lincolnshire wool merchant and was perhaps the ablest canon lawyer of his generation and his 'Constitutiones Provinciales Ecclesie Anglicane', a gloss on English canon law, was for many generations the seminal work. After study at Cambridge and preferred to numerous livings, Lyndwood first served in the household of the bishop of Salisbury, before joining the household of the archbishop of Canterbury, where he was Dean of the court of Arches. Coming to notice of King Henry VI, he was a trusted diplomat and in 1432 became Lord Privy Seal. In 1442 after the king petitioned the pope he was appointed bishop of St David's. Lyndwood was consecrated in St Stephen's chapel, the royal chapel, directly above the place where the body was found in 1852. He didn't visit his see and continued to serve in the royal household until his death.

|

| NPG D24017 © National Portrait Gallery, London |

Lyndwood died in 1446 and wrote a very illuminating will. He left his body:

'to be buried in the chapel of St Stephen in Westminster, where I received the gift of consecration, in such place as may be agreed upon between the dean and canons of the said chapel and my executors and I wish that the place of my interment may be decently ornamented for at least twelve months after my decease'.

He also asked that his executors establish a perpetual chantry in St Stephen's and the royal licence for that was granted in 1454. The chantry was to be 'in bassa capella' the lower or under chapel of the St Stephen's, for the soul of 'the said late bishop, whose body rests interred in the said under-chapel'.

It was in that very under-chapel that the body wrapped in cere-cloth was found in 1852 and in the absence of evidence of another bishop being buried in the chapel royal in the fifteenth century, the body is likely to be Lyndwood's. As for the body, in time it was reburied in the north cloister walk of Westminster Abbey.

The account of the discovery: 'Report of the Committee appointed by the Council of the Society of Antiquaries to investigate the circumstances attending the recent discovery of a body in St Stephen's Chapel, Westminster' in Archaeologia 34 (1852), pp. 406-30.

R. H. Helmholz, ‘Lyndwood, William (c.1375–1446)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/17264, accessed 4 March 2017]

Comments